Expert witness tells court RCMP officer’s use of force “reasonable”

Throughout four days of testimony in Woodstock’s Court of King’s Bench, witnesses helped piece together the chain of events on June 13, 2024, that resulted in Christina Gillis of Richmond Corner being injured and Western Valley RCMP Cpl. Andrew Whiteway being charged.

Testimony revealed a family in mental health crisis and an Indigenous woman dealing with generational trauma. Gillis is Mi’kmaq, originally from Eskasoni First Nation in Nova Scotia. The charge against Cpl. Whiteway was laid after the Serious Incident Response Team (SiRT) investigated and recommended that the situation be dealt with criminally.

The case, heard by Justice Christa Bourque from Jan. 12 to 15, hinges on one key issue: whether a police officer used reasonable force or broke the law.

The call

It was a warm and sunny June day when Gillis and Barry “Scotty” Scott, her common-law husband and a Woodstock Police Force (WPF) constable, were getting ready to barbecue at their house in Richmond Corner. Late that afternoon, Gillis’ teenaged daughter came home after being out with friends. She became violent and was assaulting family members. Gillis called the RCMP for help.

RCMP Cst. Joseph Sloan was first on scene and quickly called for backup, as the teenager had fled, barefoot, into nearby woods. Gillis told the officer her daughter was suffering from mental health issues, could be explosive, was intoxicated, and on that day had taken two-to-three times the dose of antidepressants she was prescribed.

In her statement with SiRT investigator Patrick Tardif, and on the witness stand, Gillis said her relationship with her daughter was complicated and sometimes violent. Gillis said she had been struck by her daughter in the past. Her daughter also testified that she had assaulted her mother previously.

RCMP Cst. Sara Nunes, then a six-year veteran of the force, was at the end of her shift, but responded to Cst. Sloan’s call for assistance, as did RCMP Cst. Nick Labonté-Gregory, who was a rookie officer at the time. The two members were able to arrest Gillis’ daughter and were walking her out of a field when Gillis approached them. After an exchange between her daughter and Cst. Nunes, Gillis began to scream, shouting profanity-laced insults at the female constable, getting close to the officer and pointing fingers in her face.

“It was like a bomb went off.”

“I heard (my daughter) screaming, so I went to make sure she’s not flipping out,” Gillis testified. “I hear her mouthing off to the officer, and I said to her, listen to them, listen to them, and then she hollered, ‘Mom, she thinks she’s prettier than me!’ and then she (Cst. Nunes) said, ‘I am.’ And that’s when I said, ‘What the f–k did you just say?’ Then I went around her, and I said, ‘You f—king know better than this.’ I started freaking out.”

Throughout Gillis’ testimony, Justice Bourque stopped her several times, asking Gillis to watch her language when it wasn’t a direct quote from the incident and explaining why she can’t hurl insults at the accused while testifying. Gillis was visibly nervous, sometimes belligerent with defence counsel, and had to take multiple breaks. There were times when Gillis’ testimony made her sister cry and her mother look away.

When defence lawyer T.J. Burke asked Gillis about the inconsistencies between her statements to SiRT and her testimony in court, Gillis got angry. She explained she couldn’t remember things sometimes because of the trauma she’s experienced.

Gillis told the court that Cst. Nunes’ comments brought out her “mama bear” instincts, and she was upset with the officer’s lack of professionalism.

The insults Gillis directed toward Nunes were personal, threatening, and vulgar.

Cst. Nunes told the court Gillis lunged toward her, calling her an “incompetent c-nt.”

“It was like a bomb went off,” testified Cst. Sloan, referring to Gillis’ reaction to Nunes’ comment. “That’s the only way to describe it.”

When Cpl. Whiteway arrived on scene, he could see Gillis “freaking out,” and testified that he was worried about his junior members’ safety.

He was also concerned about the “potential for violence,” telling the court that the previous November, fellow officers had to arrest Gillis under the Mental Health Act, drawing their tasers in order to get her into the police car to take her to the hospital.

Cpl. Whiteway quickly jumped out of his car and tried to diffuse the situation, “making space” by extending his arm between Gillis and his officers as he moved between them. He told Gillis to back up and let his officers do their job.

The arrest

Things escalated quickly when Gillis swatted Cpl. Whiteway’s arm away.

“That’s it, you are under arrest,” he told her. Whiteway testified he had multiple grounds for arrest, including obstruction and uttering threats.

Gillis immediately backed up and started to turn. Cpl. Whiteway testified he tried to grab her arm but only managed to grasp her shirt.

“I gave her a shove to cause her to fall so I could get better control,” he said, noting that RCMP training instructs officers to get suspects to the ground so they can gain control and handcuff them.

Whiteway said that at the same time he was pushing her down, he and Gillis stumbled over a knoll and fell.

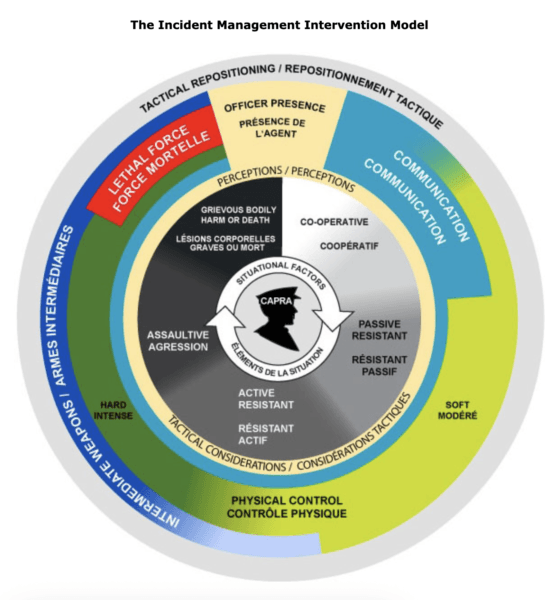

Referring to the RCMP’s Incident Management Intervention Model (IMIM), which is a guide for officers on the use of force, Cpl. Whiteway said Gillis’ behaviour on the IMIM wheel was, at this point, assaultive.

Cst. Nunes, and Cst. Labonté-Gregory testified that Gillis fell forward, face-first, and hit the ground “hard.” Gillis confirmed she faceplanted, telling the judge that Cpl. Whiteway fell on top of her.

Once on the ground, Gillis continued to resist arrest, flailing her arms and legs, attempting to kick Cpl. Whiteway, and preventing him from grabbing her arms and handcuffing her. Cpl. Whiteway testified that he was trying to get one hand cuffed before Gillis punched him in the lip.

While this was going on, Cst. Nunes and Cst. Labonté-Gregory were quickly getting Gillis’ daughter, who is still screaming and combative, to Cst. Sloan, who helped get her into a police cruiser about three metres away. Nunes and Labonté-Gregory quickly go back to help Cpl. Whiteway.

Cst. Nunes testified that when she turned around, she saw Cpl. Whiteway punch Gilis in the face. She told the court she only witnessed one strike. Cst. Sloan and Cst. Labonté-Gregory told the court they didn’t see Whiteway throw any punches.

During her testimony, Gillis said she was hit repeatedly, up to six times. Her daughter testified that from the back of the cruiser, she saw Whiteway strike her mother ten times.

Cpl. Whiteway testified that after Gillis punched him, he let go of her arm and hit Gillis.

“I struck her in the face, twice,” Cpl. Whiteway told the court.

“On a scale of one to 10,” asked defence lawyer Burke, “how hard did you hit her?”

“I don’t know, but I delivered it with force,” Cpl. Whiteway said, noting that Gillis wasn’t able to be subdued until he hit her a second time.

He also testified that Gillis was now shouting personal and threatening insults toward him, referencing his ex-wife and new partner.

Meanwhile, Cst. Nunes and Cst. Labonté-Gregory are now struggling to get control of each of Gillis’ legs, while Cpl. Whiteway tries to get her other arm out from underneath her body so he can get Gillis handcuffed.

Family intervention

WPF Cst. Scott testified that he was in his car a few metres away and couldn’t believe what he was seeing. At one point, he thinks he should capture the event with his phone, but decides against it, telling the court he didn’t want to take his eyes off what was happening.

He tells Justice Bourque that he witnessed Cpl. Whiteway use what’s called an armbar takedown on his wife.

Eventually, Cst. Scott gets out of his vehicle and approaches the officers. Cst. Labonté-Gregory and Cst. Nunes are now on high alert. They don’t know he’s a police officer, and are trying to hold on to Gillis’ legs while assessing the threat he might pose. All three officers are still on the ground trying to arrest Gillis.

“I kneeled by (Gillis),” testified Cst. Scott. “Her head was covered in blood. I said stop f—king resisting.”

Scott told the court he then grabbed her hands and helped Cpl. Whiteway handcuff his wife. Once she was secure, he got up and walked a short distance before collapsing.

“I was overwhelmed,” he said, trying to contain his emotions.

Under cross-examination, Cst. Scott testified that he’s known Cpl. Whiteway since they were young. The two not only worked together as officers through the Woodstock Integrated Enforcement Unit, but also travelled to Boston with a group of friends to attend ball games.

“I consider him a friend, not only a work colleague,” he told the court.

Twice, Cst. Scott broke down on the stand. He admitted the ordeal has been “a struggle” for his family and testified that he was “caught in the middle” with being a husband, father, and police officer in this circumstance. He also noted his wife’s difficult past and the mental health struggles his family has experienced.

“It’s been hard,” he told the court.

Statements vs. testimony

Throughout his testimony, Cst. Scott’s recollection of events was challenged by the defence. The details in Scott’s initial interviews with SiRT investigator Tardif did not always align with his trial testimony.

Defence lawyer Burke accused Cst. Scott of “cherry picking” what he was choosing to remember. Scott corroborated his wife’s evidence, stating he saw Cpl. Whiteway strike Gillis six times.

“You understand what perjury is, right?” Burke said, after pointing out inconsistencies.

In his SIRT statements, Scott said he was okay with his wife’s arrest.

“Great, she’s cuffed,” he told the investigator. “Let her f—king calm down.”

Under cross-examination, Cst. Scott said that when Gillis and Cpl. Whiteway were fighting on the ground, he never shouted for Whiteway to stop. After his wife was arrested, and while officers were still on scene, Cst. Scott also testified that he never spoke to any officer about Cpl. Whiteway’s use of force, nor did he file any official complaints through formal policing channels about the incident in the days afterward, and he and his wife have not filed a civil suit against Cpl. Whiteway.

Burke asked Scott whether he thought there was a conspiracy among the RCMP officers on scene that day.

“That’s my testimony,” he answered. “That’s what happened.”

The court heard the altercation was quick. Officers testified it was approximately 30 and 35 seconds between the fall and the handcuffing, while Gillis told the court it could have been a minute.

“When we finally got the handcuffs on, I was winded,” said Cpl. Whiteway. “I know LG (Labonté-Gregory) was winded too.”

In the end, it took three officers and her husband to handcuff Gillis.

Injuries

Once cuffed, officers helped Gillis to her feet and began walking her to the patrol car. They immediately noticed Gillis’ face and called Ambulance New Brunswick.

Gillis collapsed before she reached the cruiser. When officers finally get her in the back seat, Cpl. Whiteway reads her ‘the caution’ which outlines her rights. She begins to spit blood all over the police cruiser’s ‘silent patrolman’ – the plexiglass and metal barricade that separates the front and back seats of the patrol car. Cpl. Whiteway then tells her she’ll also be charged with mischief, which he said set off another “bomb.”

Gillis begins screaming, kicking the doors, and banging herself off the ‘silent patrolman.’ Cpl. Whiteway asks Cst. Sloan to help him secure her feet with zipties so they can lay her down in the backseat, which might prevent her from further hurting herself. When Cst. Sloan opens the door to speak with her, Gillis suddenly becomes calm.

When the ambulance arrives, Cpl. Whiteway tells Cst. Sloan that he should handle Gillis from here on out, since he has a better rapport with her. The back seat of Whiteway’s car is so bloodied that it’s become unsafe, so plans are made to transport Gillis in Cst. Sloan’s vehicle.

Paramedics assess Gillis and clean up her face. They decide she doesn’t need further medical intervention and Cst. Sloan takes her back to the station for processing. Her daughter is still intoxicated and has begun spitting in the back seat of the patrol car she is in. When they get to the station, Gillis’ daughter gets put in a spit net, is processed, and then placed in an overnight cell.

Gillis asks Cst. Sloan to contact her husband to get her sister’s number. Her sister is a lawyer in Nova Scotia, but Gillis can’t reach her. She eventually speaks with a lawyer and complains about tooth pain. Cst. Sloan and Cst. Labonté-Gregory decide to transport Gillis to the Upper River Valley Hospital, where she is x-rayed and given a shot for pain. The doctor says there are no facial fractures, so officers take her back to the station and release her on a promise to appear. Her face has begun to swell badly, and one eye is now almost completely swollen shut.

That evening, in text messages between Cst. Sloan and Cst. Scott, Gillis’ husband expresses his gratitude to Sloan, telling him, “Thanks for everything today.”

Investigation reports

That night, Cpl. Whiteway informs his superiors of the incident, which is required when someone is injured during an arrest or while in custody. Reports are submitted, and SiRT is notified.

Days later, on June 19, officers made supplementary additions to their reports after Sgt. Dan Sharpe overhears them talking in the bullpen. Officers said Gillis had been kicking and banging herself off the ‘silent patrolman.’ It was a detail he had not read in their paperwork.

“I asked them to update their reports,” he told the court. “I was irritated (with the officers) at the time.”

Sgt. Sharpe forwarded the updated reports to his superiors and his initial SiRT contact, investigator Luc Côté.

Under cross-examination, SiRT investigator Tardif was asked by defence lawyer Burke about being the “second investigator” on the case. He admitted that Côté had been the first to read all the member reports, concluding that the case didn’t meet SiRT’s threshold for a formal investigation. That initial assessment was forwarded to SiRT Executive Director Erin Nauss, who disagreed with his findings and believed it was in the public interest to proceed, assigning the case to Tardif. His report led to Cpl. Whiteway’s aggravated assault charge.

Even though the trial stems from the arrest of Gillis, it was noted in court that she was never charged with assaulting a police officer, obstruction, or mischief. The informations were never processed – a decision made by the Crown. The RCMP appealed their decision twice; both appeals were denied.

Testimony also revealed that an internal investigation conducted into Cpl. Whiteway’s actions on June 13, 2024, found no wrongdoing.

A week after the incident, the RCMP also conducted a threat assessment after graphic and pointed social media posts made by Gillis went viral. Officers determined Gillis was not a threat.

Second medical assessment

The court heard that five days after the incident, Gillis and her sister went to the Dr. Everett Chalmers Hospital in Fredericton.

In the medical report shared in court, it was noted that Gillis made no mention to doctors that she was assaulted by a police officer. She was seen by a physician and sent for a CT scan, which found fractures along her jaw and cheekbone.

In his cross-examination, defence lawyer Burke asked both mother and daughter if they had fought after June 13, pointing to testimony that described “explosive” episodes in their relationship. Both denied being involved in any violent encounters.

Expert says force was reasonable

Cpl. Philip Scribner is an RCMP officer and an authority on police use of force. The defence called him as an expert witness. He testified he was not being paid for his court appearance and was not there in his capacity as an RCMP officer. Throughout his career, Scribner has investigated more than 300 cases involving the use of force during police operations.

RCMP officers can use force when lawfully executing their duties, as long as it is “necessary, reasonable, and proportional to the threat,” according to the Criminal Code (Section 25) and the National Use of Force Framework.

Scribner testified he reviewed each member’s report and the SiRT investigator’s report, as well as text messages, social media posts, and photographs, spending 25 to 30 hours preparing his assessment.

He explained that the number of strikes by an officer wasn’t as relevant as the details of the situation and when the force is stopped.

“When you involve emotion with anger, it becomes volatile,” said Scribner. “This situation wasn’t good for anybody involved. It’s definitely a high-risk situation. Anyone who understands the dynamics understands they are going into a hornet’s nest, if you will.”

Cpl. Scribner told the court that all the evidence indicates Cpl. Whiteway did try to de-escalate the situation, did provide orders, did tell Ms. Gillis to step back, and advised that she was under arrest prior to going “hands on.”

“It was reasonable to expect that had Cpl. Whiteway not intervened at that time,” Scribner testified, “the situation would have escalated to a point where further force was required.”

He told the court that a police officer does not have the option of losing, because being taken over in a fight could mean losing his weapons. He also said that if an officer is comfortable striking an individual in volatile situations, it is acceptable under the law.

“What allows Cpl. Whiteway to use his fists is experience,” said Scribner. “Someone will always go back to what worked for them in the past.”

He said Gillis was too close for Cpl. Whiteway to deploy a taser safely. Using OC or pepper spray wouldn’t have been a safer alternative, Scribner said, as the propellant used is so forceful that it can damage a person’s eyes.

Cpl. Scribner pointed to discrepancies between original statements and follow-up statements taken by the SiRT investigator regarding the number of hits to the face, which “didn’t seem to make sense.”

Scribner said, in his experience, people are too overwhelmed to count punches.

Cpl. Scribner also said he was “intrigued” by Cst. Scott’s statement when he said, “Okay, they’ve got her for obstruction. I’m good with that.”

In the SiRT report, Gillis said her husband saved her life, referring to his coming to the scene, telling her not to resist, and taking her hands so they could be handcuffed. Scribner said it indicated that, even after force was applied, Gillis was still actively resisting until her husband intervened.

Expert says unprofessional conduct enflamed situation

Cpl. Scribner told the court he could understand Gillis’ emotions at the time.

“Ms. Gillis is rightfully worked up,” he told Justice Bourque. “There was some unprofessional conduct, your Honour, that fired Ms. Gillis up. I’m not saying her behaviour is acceptable, but I understand and feel bad for her in this instance.”

During his testimony, Cpl. Scribner blamed Cst. Nunes for creating what he called a “dangerous situation.”

“Instead of doing the crisis intervention and de-escalation, she escalated the situation,” said Scribner. “She took an opportunity to engage in a conversation with a young adolescent girl who was already experiencing mental health anguish, and made comments that were anything but professional, which elevated the situation. What happened was that Cpl. Whiteway, who was the most senior officer on scene and was their supervisor, was forced to intervene in something that should never have happened in the first place.”

Scribner said his “heart goes out to Ms. Gillis,” noting he was a parent and that with emotions running at such a high level, he believes Gillis “likely made decisions she would not have made normally.”

“I believe it was, in fact, unprofessional conduct by a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police that put us in this situation,” he said, referring to Cst. Nunes.

Cpl. Scribner wrapped up his testimony, telling Justice Bourque that Cpl. Whiteway’s use of force during this difficult situation was “necessary, reasonable, and consistent with training and RCMP policy.”

On March 11 at 10 a.m., Crown Prosecutor Marc-André Desjardins and defence lawyer Burke will present their closing arguments to Justice Bourque. Her decision in the case is expected in late spring.