- Siblings and friends: Larry, Kimberley, Randy, and Judy, circa 1981.

- Postcard: One of the postcards Randy sent to his parents when he traveled abroad.

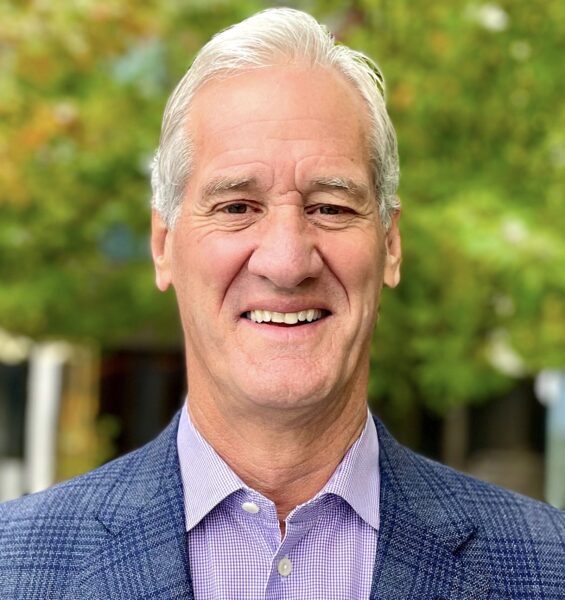

- Randy’s high school graduation photo, 1974.

- Healthier times: Randy Conners, with friend Julie Godwin and niece Hanni Bouma, Christmas morning 1983.

- Precious time together: The Conners’ siblings pose for a photo around the time Randy’s health began to fail.

Judy Bouma reluctantly watched a CBC Television show this winter. Unspeakable is a dramatic series about Canada’s tainted blood scandal. In the 1980s, more than 2,000 Canadians were infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), while another 30,000 were infected with the hepatitis C virus.

The series is based on personal accounts, books written about the tragedy, and testimony from the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Canadian Blood Tragedy, led by Justice Horace Kever. In his final report, Krever said regulatory dysfunction, corporate greed, political inaction, and bureaucratic bungling caused the tragedy.

Judy doesn’t just know the story – the Jacksontown resident lived it. Judy’s brother, Randy Conners, was a hemophiliac who contracted HIV through tainted blood in 1986. He was a key witness at the Krever inquiry and died of AIDS in 1994. He was 38 years old.

“My grandfather was a hemophiliac, and his daughter – my mother – was a carrier. Two of my aunts had children who were hemophiliacs. One of my cousins contracted hepatitis C and HIV from tainted blood but died from complications related to hepatitis C. My grandfather died, and it could have been that HIV was the cause, but we were never told…we don’t know.”

Hemophilia is a rare disorder in which blood lacks blood-clotting proteins called clotting factors and don’t clot normally. A gene mutation causes the condition.

Randy was the only Conners child to be diagnosed with hemophilia. Judy says the family’s early years were spent in Montreal. Her father was in the Royal Canadian Air Force and was based in St. Hubert. He was posted to Moncton when Judy was 16 years old.

“He refused postings quite often because he wanted to stay close to Montreal Children’s Hospital, where Randy got his care. We were all very protective of him, making sure he didn’t fall. He wasn’t allowed to play in a lot of sports for fear he could hurt himself.”

Judy still feels guilty about the time she convinced her mother to let Randy play ball with some neighbourhood kids.

“I remember he was watching us (play), and you felt so bad doing things you knew he wanted to do, so I asked my mother, “Why can’t Randy play?”

She said, “You know why.” But I kept bugging, and in the end, he was allowed to play. The first time he was up to bat, the pitcher hit him in the mouth. His mouth bled and bled, and they couldn’t get it stopped. He was in the hospital for a month. Back then, kids weren’t allowed in (the hospital to visit), only parents. You had to wait in the waiting room. We were only allowed to see him through a window in the hall.” Randy was around eight years old at the time. Judy said the memory still stings.

“I felt horrible because I was the one asking why can’t Randy ever play? That guilt is still with me,” admitted Judy. “I think of that from time to time. We were all healthy, and he was always sick. We had active lives, and he didn’t. I have memories of him sitting on the couch with a bleed in one of his joints, in a lot of pain, and Mom would say to go in and play a game with him. We couldn’t do anything to alleviate the suffering. In those days, treatments didn’t give him much relief. He had to be on strong pain medications some of the time, but he never complained.” Judy said her brother’s teen years were more comfortable, partly because he was able to use CRYO Precipitate, a new treatment then, which enabled him to self-infuse at home.

“In the TV show, when a teen had a bad bleed and treated himself, that was hard for me to watch. It reminded me of my brother,” said Judy. CRYO is made from blood product that comes from as few as a dozen donors. It is harder to store and administer, but it allowed home injection for the first time. Later, Factor VIII concentrate was introduced, which worked better for patients. That product was made from plasma taken from thousands of blood donors. While it was an improved therapy, it put patients at risk in the days before blood was screened and heat-treated. During the initial onset of AIDS, factor concentrates allowed for the rapid spread of HIV, and hepatitis B and C. Randy had already been using the product for years by the time AIDS was being transmitted through tainted Factor VIII concentrates.

Randy, like thousands of others, made the switch from CRYO to Factor VIII, finding newfound freedom in only having to take shots three times a week. Randy did things he couldn’t do before, like hitchhiking across Canada. In 1979, he went to the University of New Brunswick to study to become a teacher, then he moved to Halifax in 1980. Randy attended the Atlantic Computer School and worked on projects with Disabled Individuals Alliance, and the League for Equal Opportunities. He became a Beaver Leader. He met his wife, Janet, in 1985 and took a job with Veterans Affairs that same year. In 1986 he was diagnosed with HIV. A year later, he and Janet wed.

“He used the Factor VIII concentrate, so he was exposed many times,” explained Judy. “Randy lived without any symptoms for about four or five years, so his T-cell count must have been quite high.” A T-cell count is like a measuring stick that gauges how well your

immune system is functioning. T-cells are white blood cells that fight infection. HIV kills T-cells. A person is diagnosed with AIDS when their T-cell count drops below 200.

Judy said watching the TV series has stirred up many painful memories. “It showed a resident (doctor) putting two and two together. It made me angry to hear that again. They knew; they blatantly knew. The head of the Red Cross knew it could infect people, and yet they went ahead. They didn’t want to cause panic. It looked like it was all about money.” Throughout the series, there are instances where patients and loved ones hear the news. Judy said the scenes are eerily familiar.

“I remember being told. Randy called me on the phone. I didn’t know what it meant at first, and then I did some research; this was before the Internet. He sent me an article in the mail about a person in San Francisco, a gay person, being sick. He said to read it and weep. I said why – this has nothing to do with you. And he said yes, it does, and this is what it (AIDS) does to people. He knew then he was HIV positive then and that it could happen to him. He was well then, but it was upsetting to know that he would end up being just as sick as these people were getting.”

Randy told his parents, Percy and Dorothy, in person, driving from his house in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, to their home in Saint John.

“I don’t think they understood what was going to happen at the time. We never talked about it. My mother’s sisters (who had children with hemophilia) didn’t talk about it either. It was too personal, and they were very private. Their greatest fear was that it could happen to their boys as well. You didn’t want to discuss it, and you didn’t want people to know.”

Their fears were well-founded at the time. Little was known about the disease. Initial reports contained misinformation and fueled homophobia. In the early 1980s, HIV and AIDS were labeled the ‘gay plague.’ “I remember it was mentioned in church once by a visiting pastor. He commented on AIDS being a punishment from God,” said Judy, shaking her head. “I remember being so angry. I thought… you don’t know what you’re talking about. I had my bible in my lap, and I remember I slammed it shut.”

Judy’s face was flushed as she relived the anger of the moment. “Why didn’t you leave?” I asked. “I wanted to, but I couldn’t. It would create a scene. There was such ignorance at the time, and so many had the same attitude. I didn’t want anyone to know what we were going through.”

Judy feared how people would treat her family if they knew her brother was HIV positive. Despite the societal fear, Judy had none when it came to spending time with her brother. Randy, however, was worried.

“When we went to visit, I was never afraid to be around Randy. We still hugged him; we sat beside him like always. I do remember one experience, though. Randy was sitting on the deck outside, infusing. I sat down beside him. I remember he told me that I shouldn’t be sitting so close. I said I wasn’t worried, but he said you don’t know. He said, ‘I can’t take the chance of infecting someone. I wouldn’t be able to live with that.’ I remember it hurt at first. Maybe that was due to my bravado. I had seen him do it so many times before; it didn’t feel any different, but for Randy, it was different. He didn’t want us to take anything for

granted.”

Randy and his wife Janet fought for compensation. They let the media into their home and opened their lives to the public after his

diagnosis, with the hope of putting a face to the disease and stop discrimination. In 1989, the Government of Canada announced compensation for victims, and in April of 1993, Nova Scotia, thanks to the lobbying efforts of Randy and Janet was the first province to provide provincial compensation for victims of the tainted blood scandal. Judy said the family was proud of what Randy was able to accomplish but said watching how the disease transformed her brother was difficult.

“Randy changed. He was always so much fun, but then he lost his smile. Life became a burden. It’s hard to live your life when you’re in pain. There is no joy to look forward to. Randy was not a complainer, and I rarely heard him say anything. He persevered and didn’t lay his burden on anyone. Even as a child, seeing him sit on the couch in terrible pain, playing with his toy soldiers, he never talked about how much it hurt. He was such a special person.”

Judy said a memorable trip her brother took in the spring of 1989, shortly after he received compensation, was one of the few bright spots in those dark days.

“He had always wanted to see Europe. At the time, his son was in school, so Janet couldn’t go. We (his siblings) had lives and families, so we couldn’t go. He flew into Amsterdam and traveled by train through the Holland countryside to Baden, Germany, where he met friends that he grew up with. He flew a plane, went with his friend Mike to Switzerland, visited Liechtenstein, then went to Paris for six days and spent an entire day touring the Louvre. He went back to Amsterdam and flew home –

by himself, and he wasn’t well at the time,” said Judy, smiling and shaking her head. She said Randy pushed himself to achieve his dream, knowing there’d soon be a time he could no longer travel.

“He had a wonderful time,” she added, sharing copies of postcards Randy sent to his parents. “They show how much joy he got from that trip.”

As Randy’s health began to fail, family visits became more frequent. As her brother was suffering from pneumocystis pneumonia, or PCP, in January of 1994, Judy said he broke more bad news to the family. “Janet (his wife) was HIV positive. That was a very big blow to Randy. Little was conveyed to people about transmission. He went to his death with a lot of pain, but I think it was related more to guilt than to hisown suffering.”

That month he was told he had six months to live. Around the same time, new anti-viral treatments were being developed. It gave hope to Janet, but Randy’s body was too weak at that point.

“I remember saying to Janet that if he could have survived another six months, maybe he could have been helped, but he was so sick,” recalled Judy.

Despite Randy’s rapidly failing health, he remained an advocate for victims of the tainted blood scandal. His last brave act was a trip to Toronto to testify at the Krever Inquiry in March of 1994. Despite family concerns about his poor health, Judy said he was adamant about testifying. News reports from his testimony spoke of his gaunt and trembling appearance; how he spoke in a hoarse whisper. His body may have been frail, but his determination was strong.

“I made the exhausting trip to Toronto instead of waiting for the commission to come to Halifax because I didn’t know if I’d still be

alive in June, quite frankly,” said Randy to Canadian Press reporters covering the hearings. “It’s just plain murder, what they did; giving

out product that they knew was going to kill you. I just don’t understand how people can do that.”

“I’m very weak,” he said to Justice Krever, over nearly three hours of testimony that reporters said was punctuated by sharp coughing. “I’m very tired. My voice isn’t very good because of the tubes that were down my throat.”

At the hearing, Randy spoke of his frustration and bewilderment at being infected with the virus that would eventually kill him.

“If I’d known you could catch HIV and AIDS from the product, I was taking, and it was going to kill me, I certainly wouldn’t have taken it.”

Randy died, at home, six months later, surrounded by his family. “Janet wanted us to come,” remembered Judy. “When we arrived, we thought we were going to have time with him, but he went quite quickly. We never did get to talk to him. He had dementia by then and couldn’t communicate much.”

The memories of those days remain the most painful of Judy’s life. “When Randy was dying, my mother mostly stayed in another room by herself. She couldn’t bear to be in the room with him for very long. When he was actually dying, I said, Dad, you have to come. Dad was pacing the hallway. He went and got Mom. My mom had always been stoic. She was one to never show emotion, but when Randy died….”

Judy is overcome; the pain of the moment is visible on her face. “My mother was keening….”

Judy can no longer speak. Taking time to wipe her eyes and clear her throat, she attempts to finish her thoughts.

“My mother had locked herself away, days before. Randy had something wrong with him for so many years and my parents were so protective of him, and they did everything they could to keep him healthy, and still, he never had a chance. He was so young. She held it in for so long, that when she let go, she couldn’t help herself. I had never seen her like that before. She was like an animal. It was a low cry, she was in such intense agony. Dad wrapped his arms around her to comfort her. They shared their pain.”

We sit in silence for a few moments, both transfixed on her parents’ agony.

“Were you angry?” I asked, breaking the pall.

“I don’t think there was anger. We didn’t say a lot of angry things; we were just dealing with the loss and getting through it. When Randy was sick, that was our goal, to help him get through it.”

Having the media involved throughout the Conners’ battle for compensation sometimes made the family’s private moments very public. “When we were walking out of his home, after Randy died, we were met by a reporter who said, ‘You must be Randy’s family, I’m a reporter from such and such a paper. Would you answer a few questions?’ I remember saying ‘No, it’s too soon.’ I think Janet spoke with them after.”

Judy said the news reports felt surreal.

“The media was involved all along, so his death made the news. When we were driving home from his house just after he died, we heard it reported on the news that he had died. Dad just quietly turned off the radio. We were heading home to get clothes and pack to return for the funeral; I wanted to talk about it, but my mother said no – if we talk, your father won’t be able to drive. We never really talked about it again.”

That week, there was another loss in Judy’s family.

“The day before Randy died, my mother-in-law died. I called my husband to say that Randy was dying, and I would be there a bit longer, but couldn’t reach him. I called his work and they said he wasn’t in. I said that was odd, and asked if he was sick. They said no, his mother died. That’s how I found out.”

Judy had a difficult decision to make – which funeral to attend. “I remember talking to her a week before, and she said she was so sad to hear about my brother. I didn’t know that was the last time I would speak with her. My kids went to their grandmother’s funeral with their dad, but I had to be there for my parents at Randy’s funeral. I’d like to think she would have understood. That was such a difficult thing, not to be there for my husband, but I had to be there for my parents.” She said her parents never got over the loss. Judy’s mother died in 2014.

“She was very sick in the end, but I think the knowledge that she and Randy would be together again made it easier. Randy was a very vibrant personality. He laughed a lot – his stories were so hilarious – he was captivating, making you feel you were right there. There were times when he made me laugh so hard. I’m not a person that lets go easily, but he enjoyed everything so much, so everyone enjoyed him. There was peace for her in knowing she’d see him. He was her baby boy.”

“What did Randy’s life and death teach you?” I asked.

“That’s a hard question. I haven’t walked away with bitterness. My daughter is a doctor; I’m not blaming the medical profession. It was at the highest level, the highest person up in the Red Cross, and the Red Cross does good work too, but it was a bad decision made by people who didn’t see the big picture because it wasn’t their families. It was about money. But there was a big family lesson, too. We are stronger than we think we are. It was terribly painful and stressful, but the pervading feeling in that deathbed room was love. There was so much love all around. We each supported one another, and we got through it. We helped Randy get through it. Randy would be a grandfather now. His son has three children. I think of that often – how great a grandfather he would have been. We all still miss him so much.”

SIDEBAR:

Judy Bouma: tainted Blood and Unanswered Questions

“When I first heard about the series (Unspeakable) I wanted to see it because it’s also our story, in a way. Seeing the young boys infusing, and talking about girls, it was all eye-opening to me. We saw what Randy coped with, but I think we forgot young boys died of AIDS. Several thousand hemophiliacs died of AIDS. This was a time before social media and computers. So I think if it happened now, it would be a lot different. People would have been talking about it, and maybe it would have been stopped sooner. We’ll never know.

Watching this has brought up the anger again. Even the hemophiliac magazine that came out monthly told them to keep using the blood products and that the blood supply was safe. They could have told people to go back to using CRYO, which was safer, but some could have used nothing and would still be alive. The head of the Red Cross knew. He knew! He knew there was a chance of contamination; he even allowed people to think they were safe, and they weren’t.

I wonder what Randy would have thought about this. His son messaged me before seeing it, saying he hoped they get it right. He’s worried about them portraying it accurately. I know Randy would be glad that people are hearing the story. Watching it was like seeing a capsule of his life; what his life was like. It’s not just about tainted blood, but it’s also about the life of hemophiliacs, in a way.

I don’t give blood. When my son, Aaron, had to have surgery when he was a child, they asked me if he needed blood during surgery would we be willing to allow him to get blood. I said no, that we’d rather donate our own. The doctor said, ‘Why would you say that?’ I told him I lost a brother to AIDS. I know blood is heat-treated now and is very safe, but I still feel the same. Maybe I’m backward, but I can’t forget what happened to my family. I always wondered why they weren’t heat-treating all products back then.

Randy always said there was evidence of a list where heat-treated products went to the younger patients, and the older patients got blood that wasn’t heat-treated. They didn’t want to expose kids. They had untreated stock, and they didn’t want to destroy it because it would have cost them money.”