Province’s child and youth advocate says crisis ‘largely ignored’

By John Chilibeck, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, The Daily Gleaner

New Brunswick has largely ignored a suicide crisis among Indigenous youth, despite a report published three years ago recommending several big changes, says the province’s child and youth advocate.

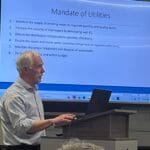

Kelly Lamrock released a progress report on Monday, Dec. 2, on the release of his office’s “No Child Left Behind” study in 2021, which contained 20 recommendations to improve the mental health of Indigenous youth in First Nations.

Indigenous youth are eight times more likely to die by suicide than other New Brunswick youth, a sad figure that shows no sign of dropping, Lamrock told reporters at a news conference at the legislature.

“The crisis is real, and the response, to be blunt, has been underwhelming.”

As an independent officer of the legislature, Lamrock was careful not to lay blame on the previous Progressive Conservative administration that lost power in October after six years.

The advocate said while direction from the top was crucial, he noted that public servants in the Health and Indigenous Affairs departments had made excuses for doing very little to improve the dire situation.

According to the “recommendation monitoring report” his office released, of the 20 recommendations, a dozen were not implemented.

Eight recommendations were described as “somewhat implemented,” while none were characterized as being significantly or fully introduced.

“The lack of action means our youth are suffering,” said Roxanne Sappier, the director of Neqotkuk Health Center in Tobique First Nation, the province’s largest Wolastoqey community, and the chair of the council that advised the advocate’s office. “We’re not meeting the needs of our families in our communities. And that has huge, huge costs.

“It’s time that this government focused on the First Nation youth of our province.”

The advocate said there were three broad areas that could be improved. He said it was important that the province put dedicated funds toward First Nation’s mental health services, arguing that money from Ottawa had never been enough to meet the needs.

Such funds, he said, should be co-managed by the province and First Nations governments, similar to a deal that was struck in 2007 between those communities and school districts, a move that saw literacy rates among Indigenous children climb by 18 per cent in just three years.

And Lamrock said mental health services should address the unique needs of Indigenous youth, pointing to pilot programs in Tobique and Elsipogtog, the province’s biggest Mi’kmaq First Nation, that have shown some success but haven’t been expanded to other communities.

Former lieutenant governor and retired judge Graydon Nicholas laid blame squarely on the Higgs Tory government.

“The past government, to me, was totally, totally unacceptable for our people,” said the Tobique elder. “There was no trust, no confidence and a lot of paternalism.”

Rob Weir, the newly elected Tory MLA for Riverview, was the only politician from the three parties to attend the report’s release.

A former executive assistant to former Tory MLA and health minister Bruce Fitch, Weir said he couldn’t speak for the previous government as he wasn’t in cabinet discussions.

“I wouldn’t want to guess because the answers to things are sometimes complicated,” he told reporters. “I will guarantee that moving forward, I will be an advocate for listening to the issues that we have and solving problems.”

Nicholas said there still wasn’t enough government funding to meet “the desperate needs” of First Nations when it came to mental health services.

As a starting point, the jurist recommended that the auditor general look into past provincial governments, going back to the Richard Hatfield Tory administrations of the 1970s, to figure out what had happened to all the funds it had acquired in the name of Indigenous people from the federal government.

Nicholas pointed out that federal transfer payments to the New Brunswick government rely in part on a formula that looks at the number of Indigenous people, but he said those funds were always put into the province’s coffers for general revenue and not dedicated solely to First Nations.

“When that money flows to Fredericton here, we don’t see a cent of it. Why? I’ve always called it ‘unjust enrichment’ that the Government of New Brunswick has been receiving for many, many years, with very little accountability and very little benefit to our people.”

Nicholas said he was putting his trust in the new Liberal government to do the right thing.

The Liberals said in their provincial election platform they were committed to working with First Nations to improve youth mental health. Rob McKee, the minister responsible for addictions and mental health services, has been named as the lead on the file.

Premier Susan Holt’s mandate letter last month to McKee says he is to “work in partnership with First Nations to co-create and implement mental health and addiction programs that meet culturally safe First Nation service and practice standards of care.”

Brunswick News asked for an interview with McKee, but received a statement instead.

“We recognize the need to take action. A number of initiatives are underway to address recommendations pertaining to Health,” the minister said, adding that they were in various stages of development.

“We weren’t making the gains we had hoped for from the last government,” Sappier said. “It’s very challenging without that support from the top. So, we’re very hopeful that now that we do have a mandate from this government supporting this work, that we will make some gains that we’ve been waiting for, for a long, long time.”

The first recommendation of the 2021 report was for the province to ensure the Mi’kmaq, Peskotomuhkati and Wolastoqey languages be formally recognized and supported by legislation. A part of the change would see better funding for language revitalization programs. With most fluent speakers elderly, all three languages are at risk of going extinct.

“Our language is medicine,” Sappier said. “Our language is health. Our language is foundational to our meaning, our belonging, our purpose and our hope. The fact that it’s not even recognized in this province in our homeland is very disappointing. And we’d like to see that change because this is our homeland.”

Green Leader David Coon complained there was little accountability to ensure the provincial government follows through on the advocate’s recommendations.

“The auditor general makes recommendations, and the public accounts committee makes sure they’re implemented. We haven’t got that mechanism for recommendations for the child and youth advocate, and we need it.”

Coon noted that the Gallant Liberal government created the Standing Committee on Social Policy, which would be an ideal forum for hearing such matters, but it has never met in its nine years of existence other than to elect a chair, vice chair and membership.

The Office of the Child Youth Advocate came out with the report three years ago in the wake of the death of Fredericton teenager Lexi Daken, who had sought treatment at the emergency department of the Dr. Everett Chalmers Regional Hospital in February 2021. She left after eight hours without having received any mental health intervention and died less than a week later by suicide.

Although Daken wasn’t Indigenous, the office decided to create three advisory councils to provide guidance and feedback on youth mental health in the province – Stakeholder, Youth and First Nation Advisory Councils.

Sappier, appointed chair of the council that would produce the First Nations report, wanted to pay homage to Daken’s family.

“This report never would have started without, unfortunately, the death of Lexi Daken,” the social worker said. “And so, I do want to make sure she’s always remembered as all these steps move ahead, because it’s another Christmas without Lexi for her family. And many of our people will not be with their loved ones this Christmas as well because of suicide. So, let’s not forget those people.”