Financial support sought for upkeep of Lower Jacksonville Cemetery

The Baptist Church is the largest Protestant denomination in New Brunswick and represents the biggest faith community in Carleton County.

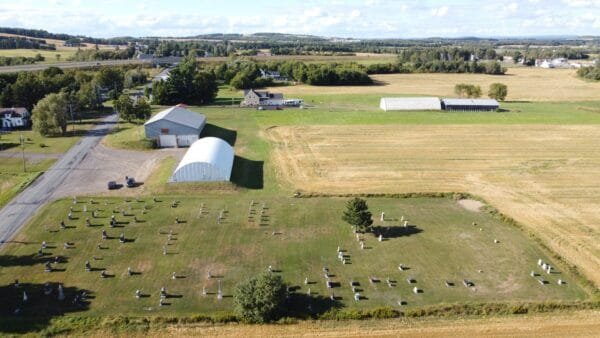

Nowhere is that strength more evident than in Jacksonville, outside Woodstock, where a modern church building dominates the landscape near the Trans-Canada Highway and two cemeteries provide final resting places for Baptist parishioners spanning generations.

One is the Lower Jacksonville Cemetery on Route 560, where 165 gravestones bear 324 names, originating from 72 local families. It’s an old cemetery with over 200 deaths recorded prior to 1960.

Family names found on the stones include Colpitts, Briggs, Havens, Slipp, Sharpe, Burpee, Cheney, Minard, Good, Green, Hayward, Kearney, Johnston, Kinney, London, McCain, McLean, McNally, Price, Seeley, Tilley, Tompkins, Vail and Bulmer. The oldest name on any stone is Joseph Risteen.

“We have started reaching out to local funeral homes to ensure they are aware of the need of this cemetery for any memorial donations,” said Marilyn Wilson, spokesperson for the cemetery committee. “We have also started contacting family members to ask for donations. With the majority of the interments taking place between 1839 and 1960, it has been a challenge to find family members.”

According to the Provincial Archives, the Baptist movement began in the province in 1763 with settlers from the New England States. By 1861, it was the leading Protestant denomination in New Brunswick. A merger with the Free Baptists in 1906 created the first United Baptist Convention and set the stage for future church growth and development.

In Carleton County, the first Baptists arrived in the area in 1783, followed by Loyalists, and then by Scottish and Irish immigrants in the early 1800s.

Jacksonville was founded around 1818 and was originally part of the neighbouring community of Jacksontown. The area was named for John and William Jackson, Irish settlers who arrived in 1810 and helped open the region for farming.

A tiny Free Baptist Church opened in the middle of the village around 1839 with land donated by the Kinney family. The first pastor was Banfred Colpitts, who later served as an enforcement officer during Prohibition.

In 1848, a mine opened at nearby Iron Ore Hill, which produced iron and manganese for nearly 40 years. The minerals were smelted in Upper Woodstock.

By 1859, Jacksonville had its own post office, a schoolhouse, a tannery, a cheese factory, three stores, and a shoemaker.

In 1860, the local Baptist congregation decided to build a larger church near the site of today’s Jacksonville United Baptist Church. It was constructed to better accommodate churchgoers who were travelling by horse and wagon to Jacksontown, some distance away.

Around 1890, the little Free Baptist church was moved across the road to become a storage shed for the Palmer family. The adjoining cemetery (known as the Lower Jacksonville Cemetery) was left in the community’s care, although many Baptists were buried there.

In 1929, the Jacksonville Women’s Institute became the cemetery’s caretaker and managed funds for its care for the next several decades, until the group disbanded.

In 2001, a nonprofit corporation was formed by the community to take responsibility, but care of the cemetery eventually fell to a handful of dedicated volunteers, including Bobby Vail, Floyd Price, and Gerald Cole, who mowed and maintained it for several years. (Vail and Price are now buried there).

Wilson said construction of the Trans-Canada Highway (TCH) has made it difficult for Jacksonville residents to come together as a community. The first highway ran through the middle of the village in 1959, and the sense of division grew deeper with the construction of the twin highway and the giant overpass in 2007.

“It has separated the community so much,” she noted.

Last year, Wilson and local residents Debbie Vail-Carr and Valerie Piper decided it was time for action. They formed a committee to develop a new plan for the cemetery.

Their goal is to raise $50,000 for a perpetual care fund that can be invested to generate annual income for cemetery care. Wilson would also like to erect a columbarium designed to hold urns containing cremated remains and provide a memorial wall for families to visit.

Historical discovery

During their research, the three-member committee discovered that the Lower Jacksonville Cemetery is of significant historical importance. At the back of the property are 26 unmarked graves of descendants of Black Loyalists who once attended the little Free Baptist Church.

Their ancestors were among the free Black Loyalists who migrated northward over 200 years ago. They came to the Jacksonville area from Nova Scotia. Members of the Nelson, Francis, Norton, and Fraser families attended the little Baptist church and lived and worked at Iron Ore Hill as farmers or miners.

“Black history is well known in the area and is an established part of local society,” said John Thompson, chairman of the Carleton County Historical Society. “It’s important that we recognize and gain insight about this history.”

The AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church was established in the province in 1893 and has a rich history tied to early Black settlers. It was first founded in the United States to allow Black congregants to worship free of racial discrimination. In New Brunswick, the AME served as a cornerstone and social support for early Black settlers.

“We have a copy of the death certificate of Randolph Nelson, stating he is buried at Jacksonville,” Wilson explained. “This gentleman was an original trustee of the AME Church in Woodstock.”

Local MLA Bill Hogan, the provincial Department of Tourism, Heritage and Culture, the Town of Woodstock, New Brunswick’s Black History Society in Saint John, and REACH (Remembering Each African Cemetery’s History) in Fredericton, have all been contacted about the 26 graves discovered in the Lower Jacksonville Cemetery.

“We’re going down every road we can to draw attention to this,” Wilson stated. “We’re hoping people become aware and will care enough to help maintain it for all who are buried there.”

Jennifer McInerney-Dow, history researcher and consultant with REACH, said several Black cemeteries are located in the province. The organization is interested in the recently identified graves in Jacksonville, located in a “mixed cemetery.”

“This is something we are looking into,” McInerney-Dow said. “We want to help, but we are a small non-profit so it would depend on government support. It is a work in progress.”

“The existence of Black communities in places like Jacksonville is often times forgotten,” she added. “We need to remember that even these small rural communities were once home to Black New Brunswickers.”

Woodstock Mayor Trina Jones said the town will assist Wilson and her committee with an application to have the Lower Jacksonville Cemetery designated a historic site under the Heritage Preservation Act.

“Council would be happy to review and discuss the matter as part of our regular and required formal council process,” Mayor Jones said. “Preserving and acknowledging historically significant sites is important.

“This is the first opportunity the municipality has had to participate in this process in one of our newly amalgamated areas. We appreciate the dedication of our local community members in recognizing and caring for this site and we are committed to working through this process with them.”

Jessica Hearn, communications officer with the Department of Tourism, Heritage and Culture, said the department does not have funding for cemeteries but can provide guidance to community members in Jacksonville on the historic designation process.

Wilson said the committee also hopes to obtain a registration number for the cemetery from the Charities Directorate at Revenue Canada in order to issue official tax receipts for donations. In the meantime, the need for donations is urgent and can be made by contacting any of the three committee members or by emailing Wilson at momathome4@hotmail.com