Opponents to Miramichi Lake bass bass-eradication project fear Working Group rushing to complete poison lake before court rules on injunctions

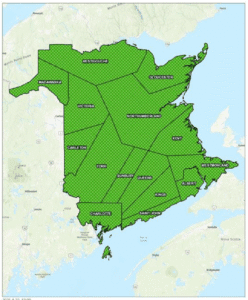

The proverbial battle of an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object may come to a head within days or hours at the ordinarily tranquil setting of Miramichi Lake in southwest New Brunswick, near Napadogan.

A group of Miramichi Lake cottage owners, First Nation representatives and members of the general public are making a last-ditch effort to stop a project designed to kill all fish in the lake and the waters flowing from it.

Meanwhile, a Working Group, including the Atlantic Salmon Federation, the North Shore Micmac Council and others, are finalizing its steps to pour deadly Noxfish II, with active ingredient rotenone, into Miramichi Lake, Lake Brook and a portion of the Southwest Branch of the Miramichi River.

The basis of the Working Group’s plan in the short term is to kill all gill-breathing fish in the waters to eradicate the smallmouth bass, consider

ed an invasive species. The long-term goal is to protect the Miramichi River’s most famous and profitable inhabitant — the Atlantic salmon.

The Working Group’s project garnered the full support of Health Canada, the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the New Brunswick Environment and Natural Resources departments.

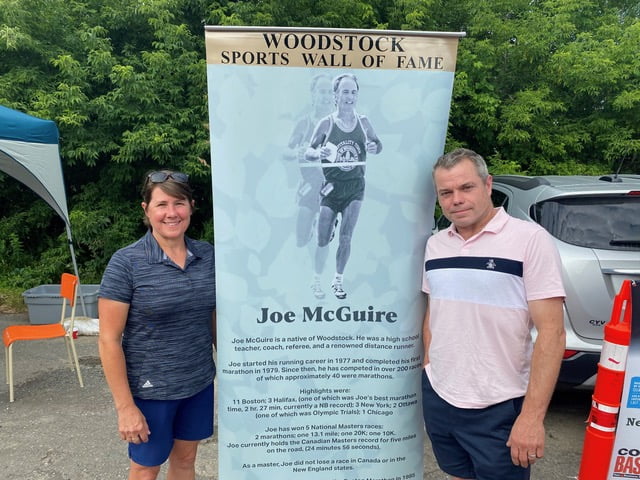

The project’s opponents successfully blocked last summer’s attempt to add rotenone to Miramichi Lake by continuously remaining on the lake and forcing the Working Group to postpone its plans until this year. Woodstock First Nation band councillor Andrea Polchies was of the Wolastoqewi mothers and grandmothers leading last year’s protest in canoes and kayaks.

Polchies is continuing her battle again this year as the spokesperson for a group called Connecting to the Land. She, along with other paddlers, plans to maintain a 24-7 watch on the lake to keep Noxfish II out of the lake.

Polchies said she arrived two weeks ago, where she remained except for a couple of days.

Unlike last year, when the Working Group gave cottage owners and others a specific date for the planned project, it promised only 24-hour notice this year. Polchies said she has no idea when they will dump the rotenone into the waters, but it completed much of the preliminary work, such as setting docks and blocking roads into the lake.

“I don’t know. You know, they’re just that sneaky that I can’t. I can’t determine when it’s going to happen. So I said, I have to be here,” Polchies told the River Valley Sun on Friday, Aug 5.

The Indigenous group is working in partnership with the cottage owners and others. Together the project opponents filed two injunctions to stop the process, but cottage owner Trish Foster believes the Working Group will act before the court can issue a ruling.

“I fear it is too late,” said Foster. “Although the Working Group has been notified of two injunctions filed against the project, it appears, based on activity at the lake, that the poison will be applied before a judge can make a ruling.”

While the Working Group is armed with federal, provincial, and Health Canada approvals and examples of successful applications of Noxfish II and rotenone, the opponents counter with their own independent reports, studies and opinions, citing the plan as dangerous or at least ineffective.

The opponents point to an opinion from Nova Scotia biologist Bob Bancroft, who offers an extensive background in rotenone-based eradication projects over several decades, suggesting the high probability the Miramichi Lake project will fail.

“In my estimation, as a biologist, this method of killing so many aquatic vertebrates and invertebrates, in an effort to eliminate one other species, and when the probability of success is almost nil, amounts to a tremendous waste of time and money, while creating an ecological nightmare,” said Bancroft.

Cottage owner John Hildebrand and his sister, veterinarian Dr. Barb Hilldebrand, have extensively researched rotenone and bass eradication since the Working Group first announced the plan in 2019. John said that research clearly indicated the risk does not equal the reward.

While the scientific information regarding rotenone and species eradication is wide and varied, Hildebrand believes the evidence doesn’t support the use of Noxfish II in Miramichi Lake and the Southwest Branch of the Miramichi River.

Hildebrand said the final decision comes down to two central factors.

“Long-term damage, and it’s very unlikely to succeed,” he said.

Hildebrand said independent peer-reviewed studies had said rotenone and the many other chemicals in Noxfish II risk substantial long-term damage to the ecosystem.

He added that the Working Group could not assure that the lake’s native species would return as expected or if the food chain would recuperate without a broken link, affecting aquatic and non-aquatic lifeforms, including birds.

Like many opponents and experts, Hildebrand points out that the Working Group already acknowledged the presence of smallmouth bass beyond the proposed treatment area. He said that alone would nullify a complete eradication.

The Atlantic Salmon Federation Executive Director of Communication Neville Crabbe said the Working Group doesn’t have a precise estimate of the number of bass beyond the treatment point. Still, they believe the chance of bass spawning is negligible.

The Indigenous perspective surrounding the bass eradication project differs significantly among groups. The North Shore Micmac District Council, comprised of chiefs from our seven-Mi’kmaq communities, described the project as Indigenous-led conservation.

While district council spokesperson Taylor Ward said that the council stands in solidarity with the Wolastoqey Nation, representing First Nation communities along the St. John (Wolastoq) River, that bond is unclear.

Policies said most members of the Wolastoqey Nation believe the Working Group refused to listen to their views.